Quantitative vs. qualitative: a little goes a long way

Paying attention to a few simple quantities, and using them for decision making, can lead to incremental, and eventually quite substantial, improvements in quality and in efficiency.

This is one of those blog posts that I finally can move from the list of notes about what I might write about, to the published and completed section.

> [2020-08-29 Sat] On my run this morning from […] to […] I was thinking that a little bit of quantitative like OM246, knowing nutrient supply, clipvol, it goes a long way in leading to improved turf conditions.

That was my simple note. I’d like to explain it like this.

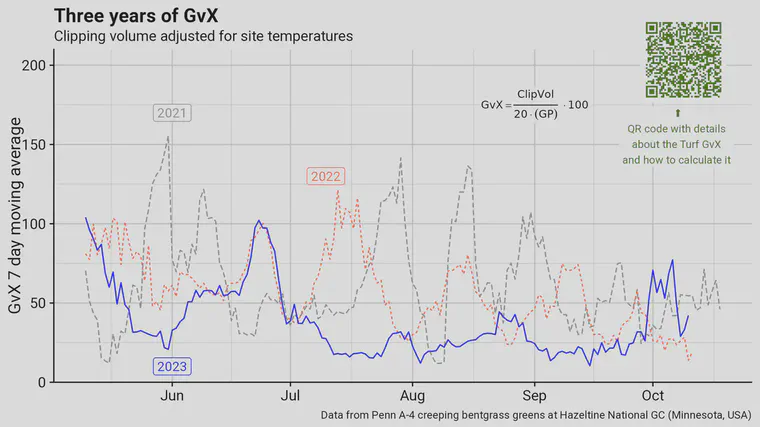

This chart shows the GvX1 for putting greens at Hazeltine National Golf Club for three consecutive years. I start at May 10 each year, because the spring growth is a bit chaotic, and go to the last mow with recorded clipping volume of the year. Note that the GvX is a simple ratio that takes the site temperatures into account. It’s the actual clipping volume divided by the temperature adjusted clipping volume.2

What are we looking at? Well, the grey line in 2021 shows that growth was fluctuating a lot. Chris Tritabaugh, the golf course superintendent, was using the best information he had at the time to try to maintain consistent growth. But if you look at the chart, it looks like a lot of fluctuations up and down through the season. In 2022, he made some adjustments, and there is a little more consistency with the 2022 data (red line). Then in 2023 he made even more adjustments, and the GvX was more consistent, with fewer spikes up and down through the year.

Clearly this is quantitative—it’s numbers on a chart. Once you get over the hurdle of actually collecting the clippings, however, this type of information takes no additional time. It’s all calculated by a computer.

And what does this have to do about quality? What do I mean by a little bit of quantitative data goes a long way to improve quality?

First, I imagine the grass can be a little healthier when grown at a consistent rate. That’s speculation, but it seems reasonable.

Second, I think the playing conditions can be a little more consistent when the grass is grown in a way that matches the temperatures, without too many spikes up and down.

Third. and this is where it gets to the main point—making adjustments to the maintenance work based on the quantitative measurements leads to real benefits. Making adjustments to N rate based on how much the grass was growing led to a 25% reduction in clippings in 2023, compared to 2022. With 25% fewer clippings, might that lead to less requirement for disruptive brushing, verticutting, and sand topdressing? I think it’s reasonable to expect that. Let’s say those disruptive practices can be reduced 25%. That should be 25% more of the golfing season played on perfect greens. Or something like that. One might batch the disruptive work and do it intensively all at once—clearly less of that is required when the grass grows 25% less.

Fourth, this same effect can be seen with OM246 data, where simply making the effort to spend a couple hours collecting samples, once a year, can lead to putting the right amount of sand to keep putting surfaces in top condition. Or with MLSN soil test interpretation, where one can eliminate the risk of nutrient deficiencies and concentrate on difficult things.

The whole idea of this approach, which I refer to sometimes as the grammar of greenkeeping, is to make some simple measurements, find out how they change over time, and make sure they move in the direction that leads to improved turfgrass and improved playing conditions. Also, by becoming familiar with this grammar, one can compare the turf and playing conditions and growth at your site to anywhere else in the world. You probably don’t want to do that—there’s not much use for such a broad comparison. But it can be insightful, sometimes, when you become aware of, or experience, a particularly fine stand of turf, and want to know how it was produced, and how much it was growing, and under what conditions it was growing. Once you have these quantitative values, then the qualitative results follow quite easily.

The Turf GvX is observed turf growth versus expected turf growth, thus GvX. ↩︎

Grass is not expected to grow much when temperatures are freezing. Grass is expected to grow when temperatures are perfect. That’s the basis behind the GvX. Jason Haines came up with this idea—read more at the Turf GvX tag. ↩︎