Seasonal nitrogen use, how much and when?

This is a continuation of the fall nitrogen topic that I deliberately raised in a couple of blog posts. See these for some background:

Many turf managers get great results with late fall nitrogen applications. But that is not the way I would fertilize turf. I don’t expect what I write here to change anyone’s mind, or way of fertilizing – at least this year – but I hope that when early and mid- and late-fall N applications are made, you might remember this, and observe the turf next spring, and see if what I’m writing about might be right.

When I first wrote this post in 2014, Chris Tritabaugh had just shared this article about seasonal stages of bentgrass nitrogen fertilization and said that he operates along those lines, and I understand that a reason for that is to favor bentgrass over Poa annua.

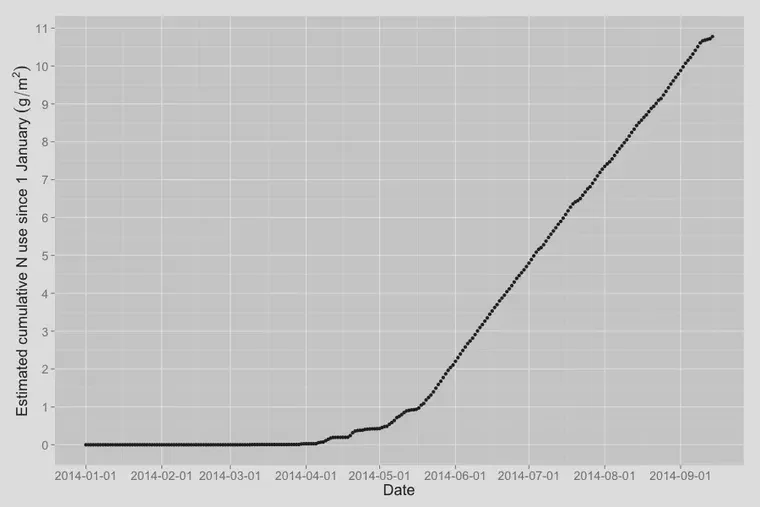

My thoughts on that paper, quickly: it seems unnecessarily complicated and I don’t understand where the “six” seasonal stages come from. That seems like an arbitrary number. One could imagine another approach with three, or seven, or seventeen stages too. I like the idea of applying as little N as possible. But I would go about that in a different way, because I think applying nitrogen when the grass can take it up gives me control over the growth. And as regards N application in the spring, I calculate that bentgrass in Minneapolis with temperatures as experienced in 2014, would require only 2 g N m-2 from 1 January to 1 June.

That 2 g m-2 of estimated use from the start of spring to 1 June is not very much. The average golf course putting green soil, based on an analysis of the MLSN database, will contain about 6.5 ppm of available nitrogen. That is equivalent to 1 g N m-2. Half the N the grass may require in spring, then, is probably already in the soil whether fertilizer is applied or not. And I suggest that ensuring the grass is well-supplied with nitrogen in autumn, and skipping a late-fall N application, is likely to supply the grass with more than enough N to perform well in spring without additional N applications. Keep in mind, 1 g N is 0.2 lbs N/1000 ft2. These are small amounts of N the grass is using when temperatures are cool.

It makes sense to me to apply nutrients approximately in the amount that can be used by the grass in the short term, or that can be held in the soil for the long term. Let me say for the purposes of this blog post that I mean short term to be 30 days or less, and long term to be more than 30 days. Late autumn N fertilization is a conspicuous departure from this demand-driven approach to fertilization.

And it seems a bit tricky and unpredictable to try to time that rather substantial application. The average N applied in Wisconsin after 1 October, in a survey by Lloyd, was 4 g N m-2. One would almost never apply that much N to high performance turf in a single application when the grass is actively growing. Applying that much N when shoot growth has nearly stopped, well, what is that going to do? If the grass takes up all of that N, then one can think of the grass as being loaded with enough nitrogen to meet the amount it would normally use in April and May and perhaps well into June. That sounds great. But there are two big concerns with that.

First, as temperatures decrease in autumn, the uptake of N decreases too. From Lloyd et al.:

The N uptake capacity of creeping bentgrass, annual bluegrass, and kentucky bluegrass declines substantially as temperatures decrease, although N uptake potential appears to be relatively high near the time after shoot growth stops. Waiting after this period greatly reduces N uptake potential. Because of the increased risk of N loss during the fall in humid, temperate regions resulting from seasonally high rates of precipitation and low rates of ET, agronomic recommendations for late-fall fertilization need to be re-evaluated.

They grew grass at temperatures normal for Madison, Wisconsin on September 15, October 15, and November 15. The N uptake 10 days after application was 73% under September conditions, 57% under October conditions, and 38% under November conditions.

So if that N is sitting around in the soil, and not taken up by the grass, it is at a high risk of leaching.

The second concern is that if such a high rate of N is applied, and the grass doesn’t take it all up, and if that N doesn’t leach, the soil will have a high amount of available N in the spring and that may contribute to an unwanted growth flush.

Bauer et al. wrote a comprehensive review of late fall fertilization. As scientific papers go, this one comes to an unambiguous and almost scathing conclusion:

The research regarding environmental losses of soluble N applied in the late fall indicate a potential for significant N losses through leaching, bringing into question the actual costs–benefits of fall-applied N. With increasing N fertilizer costs and concern of losses from turfgrass systems, it is critical that turfgrass managers understand the agronomic and physiological benefits of their N fertilizer applications. The main reason that N fertilization in the late fall is so highly regarded appears to be based on the assumption of increased photosynthesis and rooting. However, there is minimal research on turfgrass photosynthesis at low temperatures and what has been reported does not unambiguously support such benefits. Applying this notion of increased photosynthesis from late-fall N fertilization across all cool-season turfgrass zones and species without supporting research is unwarranted. Additionally, results of studies examining the influence of fall nitrogen rates and timings on root growth are variable and indicate that responses are dependent on climatic zone, seasonal variability, and turfgrass species. Studies performed in more northern climates demonstrate that root growth may not be affected by fall-applied N (Kussow, 1992; Mangiafico and Guillard, 2006). Similarly, the perception that late-fall fertilization hastens spring green-up without a surge of top growth also appears to be highly dependent on species and seasonal weather conditions. Furthermore, scant data are available defining the uptake potential of cool-season grasses in cool temperatures; what do exist indicate uptake potential is low, suggesting that recommended late-fall N fertilizer rates are too high.

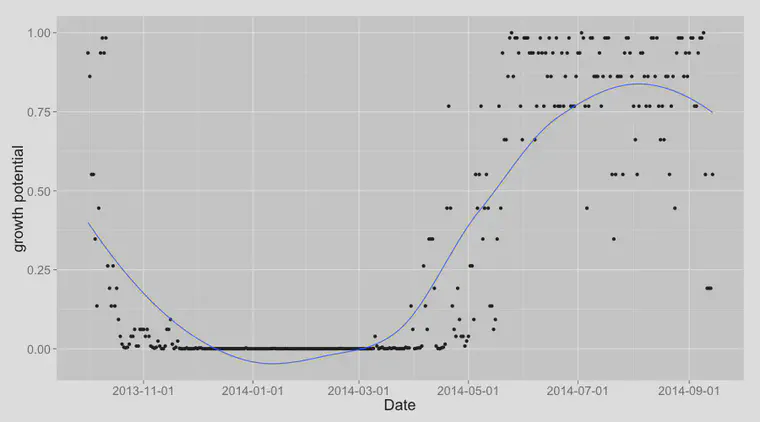

Let’s look at another chart, based on average temperatures at Minneapolis (MSP) from October 2013 through, 14 September 2014. We can look at the growth potential, based on the optimum temperatures for cool-season grass growth.

The blue line is a smooth of the daily growth potentials. The grass is expected to grow at some approximation of this chart. No growth in winter, and increasing growth in spring, and generally high but variable growth in summer, and decreasing growth in autumn. What I like to do is try to maintain a consistent amount of N in the leaves. To do that, one needs to supply the N at a proportional amount to the grass growth. The growth, naturally, depletes and dilutes the N.

I think it is likely to be the most efficient use of N, and likely to get the most predictable results, by applying N at the times when the grass can take it up. Applying a large dose of N so close to the time of year when it can’t be used – that seems pretty unpredictable.

Is there a visible response? Yes, because any nitrogen application is going to make the grass greener at some point in the future, and make the grass grow more, sometime in the future. But is all of the N used? Would a smaller dose, applied earlier in the autumn, have a similar result? Something to think about when spreading fertilizer in autumn.